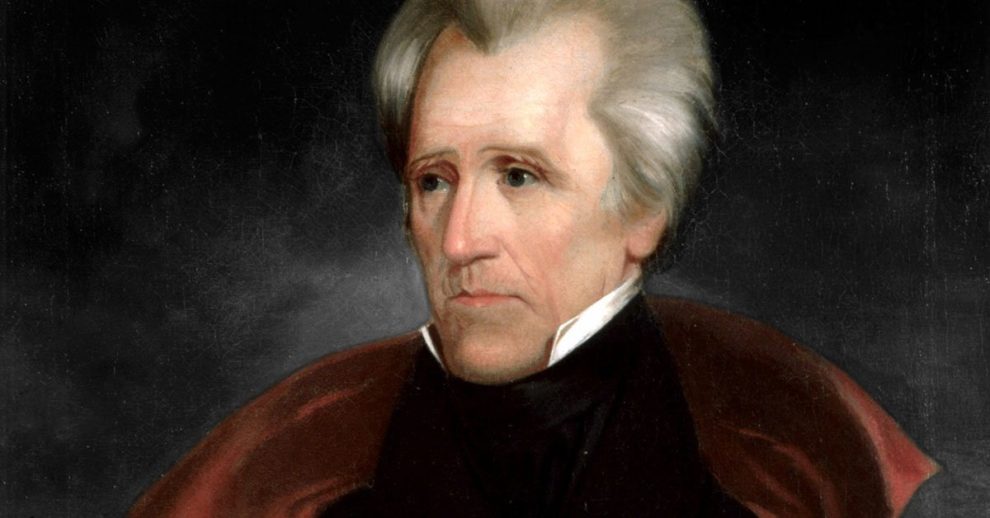

Andrew Jackson, America’s seventh president, lived a life marked by passion, controversy, and defiance. He married Rachel Donelson Robards, a devoted partner whose death just before his presidency haunted him for years. Though they had no children, Jackson filled his home, The Hermitage, with adopted and fostered sons, nieces, and wards who became his family. Known for his fierce temper, dueling spirit, and populist ideals, “Old Hickory” reshaped the presidency into a symbol of strength and the people’s will. Loved and loathed in equal measure, his legacy still divides historians as one of America’s most complex and consequential leaders.

Andrew Jackson’s Saber Scar

1. British troops captured 14-year-old Andrew Jackson near his South Carolina home in 1781 during the American Revolution. When a British officer ordered him to shine his boots, Jackson refused, declaring he was a prisoner of war, not a servant. The officer slashed Jackson across the face and hand with his saber, leaving permanent scars. Jackson carried that wound and a lifelong hatred of the British until the day he died.

2. At just 13, Andrew Jackson served as a courier for the Continental Army during the American Revolution, carrying messages through dangerous territory in the Carolinas. He was captured by British soldiers and barely survived imprisonment, disease, and starvation. By the war’s end, both of his brothers and his mother had died, leaving Jackson an orphan at only 14.

3. Born in 1767 in the Waxhaws region between North and South Carolina, Andrew Jackson experienced a life of extreme poverty on the American frontier. Unlike his predecessors, men of wealth, education, and privilege, Jackson rose from humble beginnings through sheer determination and military success. His unlikely ascent made him the first U.S. president from a poor background and cemented his image as a champion of the common man.

4. In 1815, Major General Andrew Jackson led American regulars and militia against a British assault at the Battle of New Orleans. American earthworks and concentrated fire thwarted the British attacks, leading to the British general’s death in the fighting. The British suffered over 2,000 casualties, while U.S. losses were about 70. The victory ended the British push on the Gulf Coast and turned Jackson into a national hero at the close of the war.

5. In 1829, after his inauguration in Washington, President Andrew Jackson headed to the White House as 20,000 citizens followed, and the mansion stood open to the public into the early 20th century. As the crowd jammed the rooms, they grew so rowdy, Jackson had to flee the White House to a hotel to get clear of the crush. Aides finally drew people outside with tubs of whiskey and orange juice.

6. In 1835, New York dairy farmer Thomas S. Meacham sent President Andrew Jackson a massive 1,400-pound block of cheese as a patriotic gift. Jackson proudly displayed it in the White House for over a year, allowing visitors to sample it during receptions. At his final public party in 1837, a huge crowd devoured every last bite. The smell of cheese lingered in the halls for weeks after Jackson left the office.

7. In 1835, President Andrew Jackson accomplished a feat no other leader has repeated: he paid off the entire national debt, calling it “the national curse.” Through strict spending cuts and the sale of federal lands, the U.S. balance sheet briefly hit zero. But the triumph was short-lived. A financial panic in 1837 triggered a severe depression, and by the next year, the nation owed $3.3 million once again. It has never been fully paid off since then.

8. In 1832, the Bank of the United States secretly authorized European investors to buy up the nation’s public debt, undermining the government’s plan to eliminate it. President Andrew Jackson saw the move as a direct threat to American independence. Warning that “the capitalist abroad may have an influence over the destinies of this country,” he launched a campaign to dismantle the bank entirely. The confrontation became one of the defining struggles of his presidency.

9. As a young lawyer on the Tennessee frontier, Andrew Jackson quickly earned a reputation for boldness and mischief. During one Christmas season, he organized a local dance and, in a prank gone too far, invited two prostitutes to attend alongside the town’s elite. The stunt caused an uproar among polite society, forcing Jackson to apologize and claim it had been a foolish joke.

10. In 1806, Andrew Jackson faced Charles Dickinson in a duel after Dickinson insulted Jackson’s wife, Rachel. Jackson let his opponent fire first and took a bullet to the chest, then calmly aimed and shot Dickinson dead. The act was so deliberate that many called it cold-blooded, and Jackson became a social outcast. Over his life, he fought in as many as 100 duels, so many that people joked he “rattled like a bag of marbles” from the bullets lodged in his body.

Rachel Jackson’s Election Tragedy

11. During the brutal 1828 presidential election, Andrew Jackson’s opponents accused his wife, Rachel, of adultery because she had married him before her first husband’s divorce was finalized. The scandal and relentless public attacks drove her into depression, and she died of a heart ailment just weeks before Jackson took office. At her funeral, a grief-stricken Jackson declared, “May God Almighty forgive her murderers. I never can.”

12. In the 1830s, Andrew Jackson’s opponents mocked him as a “Jackass” during his campaign against John Quincy Adams. Instead of taking offense, Jackson embraced the insult, using the donkey as a symbol of stubborn strength and the workingman’s grit. His campaign posters proudly featured the animal, turning ridicule into branding. Decades later, in the 1870s, political cartoonist Thomas Nast cemented the donkey as the enduring emblem of the Democratic Party.

13. Andrew Jackson distrusted paper currency, which in his time was printed by individual banks and often fluctuated wildly in value. Believing bankers were exploiting ordinary citizens, he championed gold and silver coins instead. Jackson even vetoed the charter for the Second Bank of the United States, famously declaring, “I will kill it,” and later boasted, “I killed the bank.” Ironically, since 1928, his portrait has appeared on the $20 bill, the very paper money he despised. There are no known records from the American Treasury Department to indicate why Andrew Jackson was chosen to replace Grover Cleveland on the $20 bill back then.

14. After his wife Rachel’s death, President Andrew Jackson asked his 21-year-old niece, Emily Donelson, to serve as White House hostess. Despite her youth, she quickly won admiration for her elegant gatherings and refined hospitality. Guests praised the food, wine, and lively atmosphere she brought to the Jackson administration.

15. After the Battle of Tallushatchee in 1813, Andrew Jackson discovered a Native American toddler lying beside his dead mother. Moved by the scene, he brought the boy, named Lyncoya, back to his Tennessee home, the Hermitage. Jackson raised Lyncoya alongside his adopted sons and treated him as part of the family. The child later died of illness as a teenager.

16. In 1829 Washington, the wives of President Andrew Jackson’s cabinet, led by Floride Calhoun, shunned Margaret “Peggy” Eaton, the wife of War Secretary John H. Eaton, over controversy surrounding her marriage. Jackson, enraged by the social boycott and mindful of attacks once aimed at his own late wife, pressed the cabinet families to accept her. The standoff only deepened, crippling official dinners and social functions across the administration. By 1831, the Petticoat affair had triggered a mass resignation that effectively disbanded Jackson’s cabinet.

17. In 1814, at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, a Cherokee warrior named Junaluska saved Andrew Jackson’s life. Junaluska rallied his men, waded across the Tallapoosa River, seized the enemy’s canoes, and helped secure an American victory over the Creek Nation. Jackson owed his survival and success that day to Junaluska. Two decades later, as president, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, forcing the Cherokee from their homelands in North Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee to what is now Oklahoma. This deadly march, remembered as the Trail of Tears, claimed up to one-third of the Cherokee people. Junaluska, who had fought for Jackson, was among those driven west. He escaped twice, walking hundreds of miles through the mountains to return home. By then, the Cherokee, who had built farms, schools, a writing system, and even a constitution modeled on the United States, had been destroyed as a nation. Though Junaluska lived on as a chief in his homeland, the betrayal cut deep. Many Cherokee still refuse to use the U.S. twenty-dollar bill bearing Jackson’s face, honoring instead the memory of the man who once saved him.

18. In 1833, Boston’s mood turned against President Andrew Jackson after he vetoed the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States, a move that hit New England merchants with financial hardship. When the Charlestown Navy Yard installed a new Andrew Jackson figurehead on the USS Constitution, locals called it a disgrace and even threatened the carver. In 1834, Captain Samuel Worthington Dewey rowed out, climbed aboard, and sawed off the figurehead’s head, then delivered it to Washington.

19. In 1835, as President Andrew Jackson left the U.S. Capitol after a congressman’s memorial service, a house painter named Richard Lawrence stepped from the crowd and aimed a pistol from just feet away. The gun misfired, so Lawrence drew a second pistol and pulled the trigger; it misfired too. Investigators later deemed both weapons in working order and calculated the odds of the twin failures at about 125,000 to 1. Jackson lunged at Lawrence with his cane while bystanders subdued the would-be assassin, marking it the first attempted presidential assassination in U.S. history.

20. In 1831, Malay raiders from Sumatra attacked the American merchant ship Friendship, killing three crew members and looting its cargo of pepper. Outraged, President Andrew Jackson dispatched the warship USS Potomac to deliver retribution. The vessel sailed halfway around the world, stormed the offending village, destroyed its forts, and burned local ships. The assault crushed further attacks on U.S. traders and marked one of America’s earliest overseas military actions.

Lafayette’s Pistols and Jackson’s Promise

21. In 1778, French officer Marquis de Lafayette gifted George Washington a finely crafted pair of pistols during the Revolutionary War. Decades later, those same pistols found their way into Andrew Jackson’s possession. When Lafayette visited Jackson in 1825, he immediately recognized the weapons as his old gift to Washington. Honoring their shared legacy, Jackson’s will returned the pistols to Lafayette’s son.

22. During the Nullification Crisis of 1832, South Carolina threatened to secede over federal tariffs, and Vice President John C. Calhoun backed the rebellion. President Andrew Jackson, fiercely defending the Union, issued a blunt warning: “If you secede from my nation, I will secede your head from the rest of your body.” His hardline stance crushed the movement and forced Calhoun’s resignation, proving Jackson’s resolve to keep the United States intact.

23. President Andrew Jackson’s beloved parrot, Poll, was known for mimicking his master’s colorful language. When Jackson died in 1845, Poll was brought to his funeral at the Hermitage. The bird began loudly swearing and shouting profanities picked up from years with the Jackson. Embarrassed mourners had to remove the parrot before the ceremony could continue.

24. At the end of his 8-year presidency, Andrew Jackson’s famous regret was, “That I have not shot Henry Clay or hanged John C. Calhoun.” Clay, a powerful senator from Kentucky, had struck a political deal that helped John Quincy Adams defeat Jackson in 1824, an act Jackson called the “Corrupt Bargain.” Calhoun, his vice president, later betrayed him by backing South Carolina’s threat to secede during the Nullification Crisis.

25. After leaving the presidency in 1837, Andrew Jackson retired to his Tennessee estate, the Hermitage, where he managed his farm and corresponded fiercely about politics until his death. There Jackson suffered from severe edema (then called “dropsy”), a symptom of congestive heart failure, and multiple other chronic ailments—including lingering wounds from duels and war. He died in 1845 at the age of 78.

Add Comment